Laparoscopic Transabdominal Cerclage

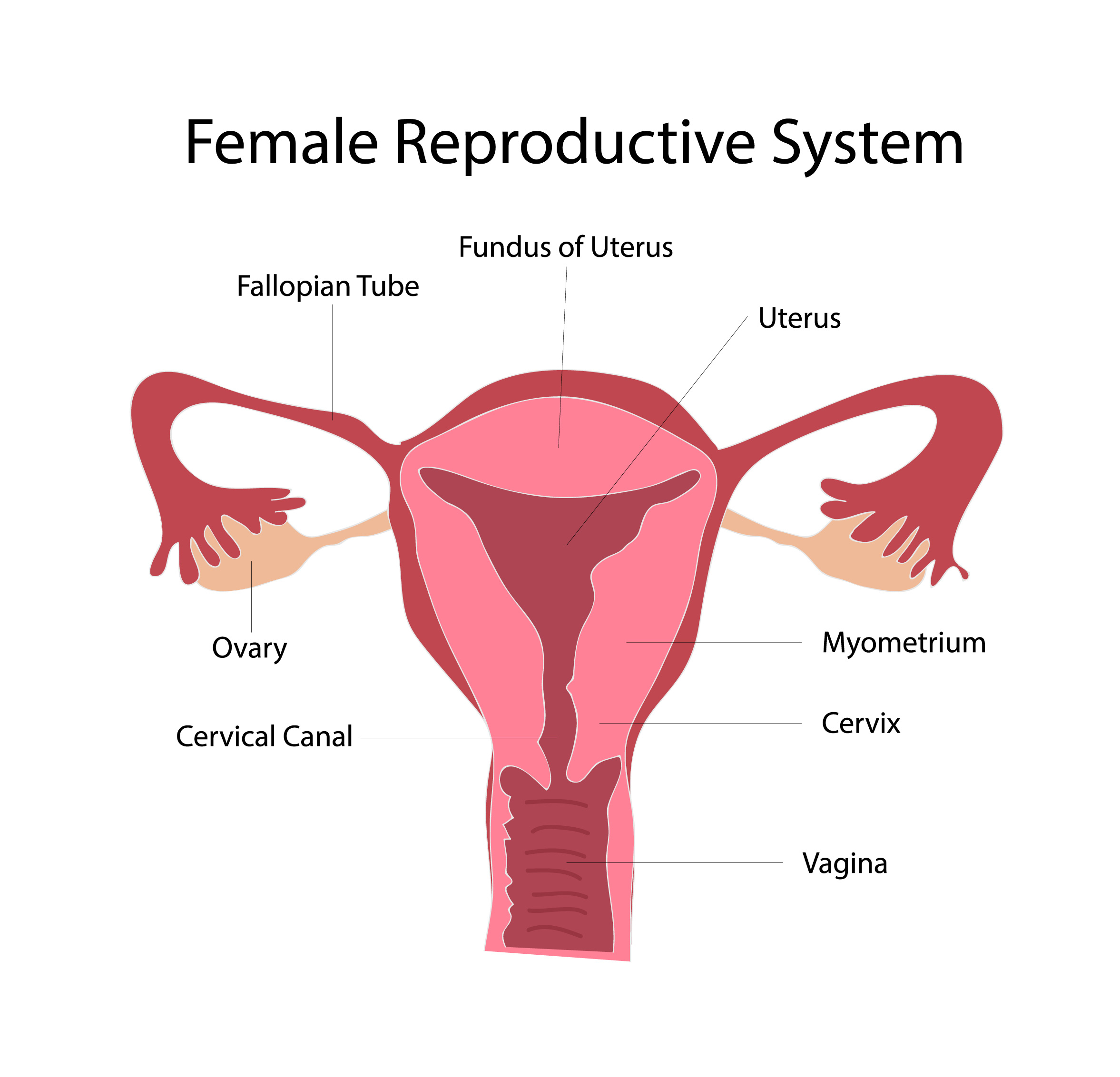

The Laparoscopic Transabdominal Cerclage (TAC) is a surgical procedure to treat cervical insufficiency. A suture is placed around the cervix at its uppermost part near the transition with the uterine body. This level cannot be reached from the vagina hence the abdominal approach.

Cerclage, a purse string suture around the cervix, was initially proposed for the treatment of cervical insufficiency in the 1950s when the procedure was done accessing the cervix through the vagina.

The Transabdominal Cerclage was introduced in the 1960s as an alternative for women who could not have the transvaginal procedure. The main reasons why this can be the case are women who had surgery where large portions of the cervix were removed or women in whom a transvaginal cerclage has failed.

The procedure was initially performed as an open Transabdominal Cerclage through an incision similar to the one used to perform a caesarean section. With the advance of new technologies and the ability to safely perform more complex laparoscopic surgery, this approach has been used to perform the Abdominal Cerclage in a less invasive and less traumatic manner. Since the late 1990s, Transabdominal Cerclages are being performed via laparoscopy (keyhole surgery) rather than laparotomy (open surgery).

The indications for Transabdominal Cerclage can vary, but it should be considered as an option in cases where:

- There is a consistent history of Cervical Insufficiency, i.e., cervical dilatation and subsequent fetal loss or premature delivery in the absence of uterine contractions.

- A Transvaginal Cerclage done in a previous pregnancy has failed.

- The cervix is short or very irregular, usually after surgical procedures such as trachelectomies or cone biopsies and/or previous transvaginal cerclages.

The surgical procedure

The procedure is performed under general anaesthesia through an operative laparoscopy with 4 incisions measuring 5 mm each, one for the camera and three for the instruments.

The surgeon identifies the bladder and the ureters and dissects the anatomical spaces around the cervix exposing the uterine arteries.

A mono-filament, non-braided polypropylene suture is then passed twice around the cervix at the level of the uterine isthmus medial to the uterine vessels to create a double loop with the knot tied at the back of the cervix. The suture is chosen because of its minimal tissue reactivity and proven durability.

The preferable time to perform the cerclage is when the woman is not pregnant. This is known as pre-pregnancy cerclage or interval procedure. The advantages of operating the non-pregnant uterus are its smaller size, fewer and smaller blood vessels and easy manipulation. In addition, there are obviously no concerns for the fetus. Some women only find out that they need a transabdominal cerclage once they are already pregnant. In this case the operation can be done during pregnancy up until 10 weeks gestation. The surgical technique is slightly modified to account for the pregnant uterus, but the outcome is very similar.

Surgical risks and potential complications

As with any surgical procedure, the main risks are: excessive bleeding, infection and damage to nearby organs such as bladder, bowel and large vessels. The possible consequences are: excessive bleeding may require a blood transfusion; an infection of the surgical incisions may require the use of antibiotics; damage to the bladder, if diagnosed and sutured during the procedure, usually heals well does not have any consequences; damage of bowel and ureters may require more surgery by a colo-rectal or urologic surgeon respectively and increased hospital stay.

Post-operative care after laparoscopic TAC

The following document outlines the post-operative care after a laparoscopic TAC.

Pregnancy management after laparoscopic TAC

The following document describes the guidelines for management of pregnancy in women who have a TAC.

Obstetric outcomes in women who had a TAC

Dr Ades introduced the laparoscopic transabdominal cerclage to the Royal Women’s Hospital in 2007.

As of January 2021, he has performed more than 400 procedures, one of the largest series in the world.

The outcomes of the first 24 pregnancies was published in 2013 (Laparoscopic Transabdominal Cerclage – a 6 year experience. Ades A, May J, Cade TJ, Umstad MP. ANJOG DEC 2013 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24359150 ). The success rate of 96% baby home was very promising.

In 2015, Dr Ades and colleagues, published an article comparing the outcomes of 54 pregnancies with TAC done via laparoscopy with 30 pregnancies where the TAC was done via laparotomy (Transabdominal cervical cerclage –laparoscopy versus laparotomy. Ades A, Dobromilsky KC, Cheung KT, Umstad MP. JMIG, April 2015 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25934056 ). Both procedures reported success rates close to 100%. The women in the laparoscopy group had smaller surgical incisions, less post-operative pain, less time in hospital and faster recovery. The laparoscopy has since become the preferred option.

In two studies published in 2018, we report the outcomes of 121 pregnancies where the TAC was placed before pregnancy (Laparoscopic transabdominal cerclage: Outcomes of 121 pregnancies. Ades A, Parghi S and Aref-Adib M. ANZJOG, 2018 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29359499 ) and 19 where the TAC was placed in women who were already pregnant (Laparoscopic transabdominal cerclage in pregnancy: A single centre experience. Ades A, Aref-Adib M , Parghi S and Hong P. ANZJOG, 2018 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29984840 ). The success rates were 98.5% and 100% respectively.

There were no cases of blood transfusion, no bowel or ureteric injuries and no other major complications.

If you require the full text of any of the publications, please email us on admin@agoracentre.com.au and we can send you a copy or check Assoc. Prof. Research and Publications Page.

Subsequent pregnancies after TAC

After the pregnancy, the TAC doesn’t have to be removed and can be used again for an eventual future pregnancy.

We have now data from 19 subsequent pregnancies on the same suture. (Ades A, Hawkins D) 16 women had two pregnancies and 3 women had three pregnancies on the same suture. There was one case where the membranes came through the cervix at 17 weeks on the second pregnancy and the woman lost the baby. In all other occasions the TAC held well and the pregnancy was successful.